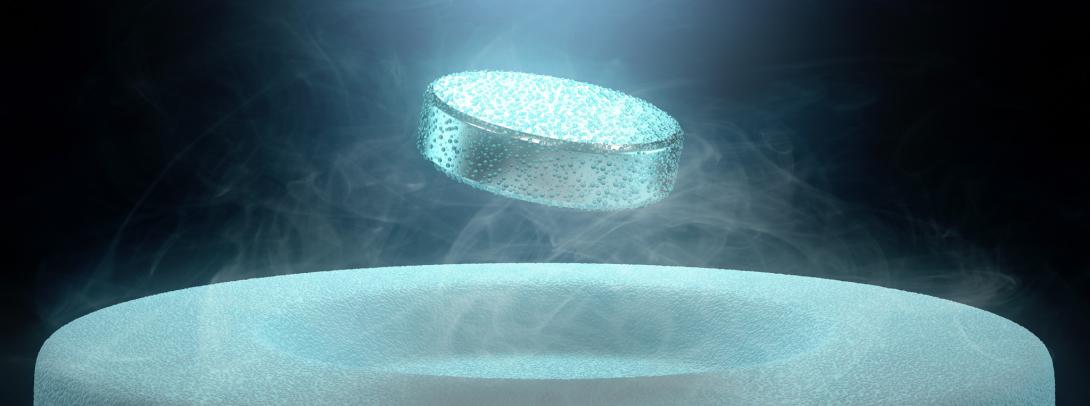

In Back to the Future Part II, the imagined future of 2015 featured flying cars and hoverboards gliding above the ground. While today’s reality hasn’t quite caught up to that vision, the underlying concept isn’t entirely impossible. One way to achieve such futuristic transportation would be through magnetic levitation powered by a special class of materials known as superconductors.

Superconductors have the remarkable ability to conduct electricity without resistance and expel magnetic fields—properties that could revolutionize transportation, energy transmission, computing, and medical technology. First discovered over 100 years ago, superconductors have remained a central focus in physics, with global research efforts working to understand their mechanisms and discover new materials with superconducting properties.

Focusing on La₃Ni₂O₇, a superconductor newly discovered in 2023, a team of NYU Shanghai researchers led by Associate Professor of Physics Chen Hanghui recently published a study in Nature Communications titled “Sensitive dependence of pairing symmetry on Ni-eg crystal field splitting in the nickelate superconductor La₃Ni₂O₇.” Their study found that the superconducting pairing symmetry of La₃Ni₂O₇ is highly sensitive to subtle variations in its electronic structure, offering new insights into the nature of superconductivity in nickelate materials and advancing the broader study of nickelate superconductors.

What is superconductivity?

A superconductor is a material that can conduct electricity without resistance, meaning no energy is lost as heat. The phenomenon of superconductivity was first observed in 1911 when scientists discovered that mercury’s electrical resistance suddenly dropped to zero at -269°C, allowing electrons to flow without any loss of energy. Later, more metals and alloys were found to exhibit superconductivity at extremely low temperatures.

Another distinctive feature of superconductors is perfect diamagnetism. When placed in a magnetic field, a superconductor generates a strong repulsive force, preventing the field from penetrating the material. In simple terms, when a superconductor is placed over a magnet, it levitates.

A Chilling Challenge

Despite their immense potential, superconductors face a significant challenge for wider application: they only function when cooled to extremely low temperatures.

Nearly a century of research has gradually raised the temperature at which superconductors work more than 70 degrees, making it possible to use cheaper and more efficient coolants. The discovery of La₃Ni₂O₇ in 2023 excited scientists because it exhibits superconductivity at -196°C, making it a new member of the high-temperature superconductor family.

The ultimate goal in this field has not yet been achieved: to discover a room-temperature superconductor. This breakthrough would revolutionize energy transmission and unlock new physical mechanisms that could potentially reshape our understanding of fundamental physics.

What causes superconductivity?

The key to superconductivity lies in a unique mechanism: electrons, which usually move independently and repel each other in normal metals, pair up in superconductors to form “Cooper pairs.” These pairs move in sync, avoiding collisions and enabling resistance-free electrical flow.

But forming Cooper pairs alone isn’t enough. Superconductivity also requires phase coherence—meaning all Cooper pairs must follow a specific symmetry pattern, much like dancers moving in a synchronized formation. Scientists have identified two major symmetry patterns:

s-wave symmetry: Imagine a round balloon expanding evenly in all directions. In an s-wave superconductor, electron pairs are evenly spread out and move the same way in every direction.

• d-wave symmetry: Picture a four-leaf clover. In a d-wave superconductor, electron pairs prefer moving in certain directions, creating a more complex pattern.

Pairing symmetry is crucial because it affects a superconductor’s stability and performance. Generally, s-wave superconductors are more stable and less affected by impurities, while d-wave superconductors can operate at higher temperatures but are more sensitive to disturbances.

Since the discovery of superconductivity in La₃Ni₂O₇, researchers have debated its pairing symmetry. La₃Ni₂O₇ is the second known high-temperature superconductor, after cuprates, with a transition temperature of -196°C. Unlike cuprates, where superconducting electrons primarily exist in a single electron layer, nickelates have a more complex three-layer structure. This suggests that nickelates may follow a different superconducting mechanism than cuprates.

Many theoretical studies have attempted to determine the superconducting symmetry of La₃Ni₂O₇, but no consensus has been reached. Some models suggest s-wave symmetry, while others predict d-wave symmetry. Chen’s team set out to resolve this debate.

The Sensitivity of La₃Ni₂O₇

In their study, the researchers used first-principles calculations, applying fundamental physics laws to determine the material’s electronic structure. They then performed gap equation analysis to compute its superconducting symmetry.

Their findings reveal that La₃Ni₂O₇’s superconducting symmetry can switch between d-wave and s-wave states due to small changes in its electronic environment.

Previous studies primarily focused on how changes in the overall electronic structure affect superconductivity. However, this study shows that even if the general structure remains unchanged, fine details can still significantly impact the superconducting symmetry.

This discovery highlights how unconventional superconductors, like La₃Ni₂O₇, are extremely sensitive to subtle electronic variations. More importantly, it suggests that experimental techniques could potentially manipulate superconducting symmetry.

“Understanding an unconventional superconductor requires balancing two critical factors: chemical complexity and correlation effects,” explained Professor Chen. “If the chemical structure is too complex, simplifying correlation effects computation becomes necessary. Conversely, if we analyze correlation effects in high detail, we must simplify the chemical description. To connect theoretical calculations with experimental results, we need to strike a balance between these two aspects—this was a key goal of our study.”

Professor Chen Hanghui is the corresponding author of the paper. Postdoctoral research fellow Xia Chengliang and Liu Hongquan ’23 (now at Brown University) are co-first authors. Zhou Shengjie ’26 also participated in the research. The study received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality.