Francisco Drohojowski, NYU Stern professor and visiting professor of finance at NYU Shanghai, first visited China in 1978 to retrace the steps of his diplomat father Jan Drohojowski—former Polish Ambassador and one of the first vocal supporters of what came to be known as the one-China policy. He shares with the Gazette his compelling family history with China.

How did your father come to meet Mao Zedong?

My father was sent to Chongqing in 1942 by the Sikorski government as Charge d’Affaires of the Polish Embassy. At the time, Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government was in power, but my father was a socialist and became a regular visitor to the Communist party stronghold in Yan'an. It was there that he befriended Communist party leader Mao Zedong, who would go on to become Chairman in 1949, and Zhou Enlai, later the first Premier of the PRC.

What did he do after his time in China?

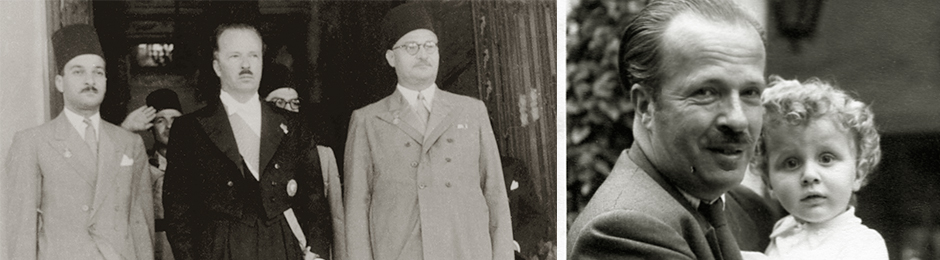

After three years in China, my father was appointed Polish Ambassador to Latin America based in Mexico City. I was born in Mexico during his time there. In 1948, he became involved in El Bogotazo, a leftist uprising that pitted Maoists against Stalinists. By now he had become a complete Sino sympathizer, and in 1951 he was appointed Ambassador to Egypt to the court of King Farouk.

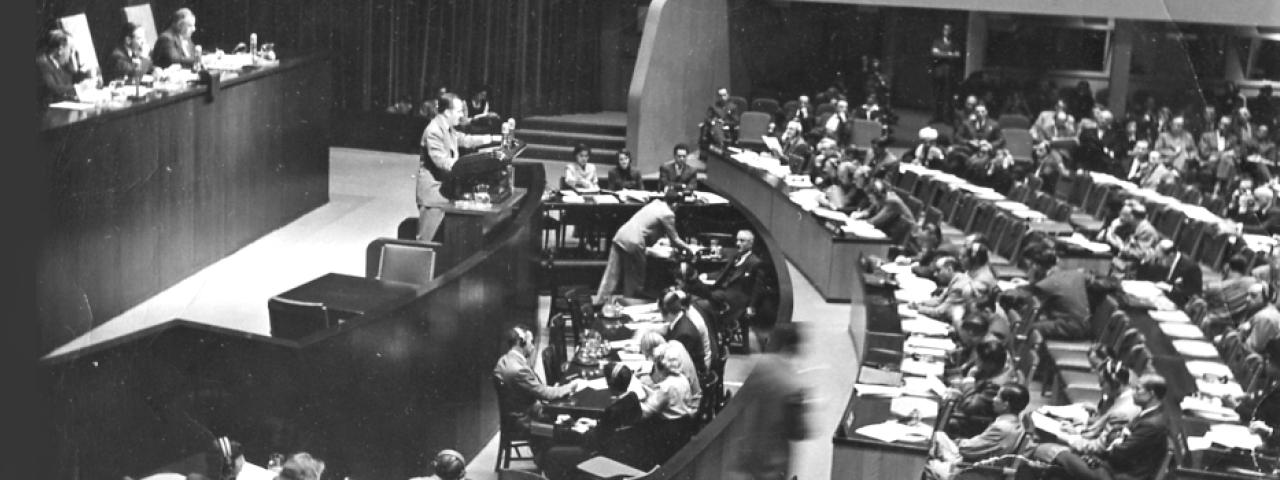

Upon our arrival to Egypt, my father went to King Farouk to present his credentials in order to receive his diplomatic accreditation. As tradition dictated, he was to be accompanied by the longest serving diplomat in the country, who at that time happened to be the Ambassador of Taiwan.

And this was a problem for him as a Sino sympathizer?

Yes. My father refused to be accompanied by the Taiwanese Ambassador because Taiwan did not exist as a nation for him. I believe this became one of the first instances of a diplomat voicing public support for what would later become known as the One China policy. He was one of the first foreign diplomats to take that position.

Six months later, the Egyptian government declared my father a persona non-grata and expelled him from the country on charges of conspiring against the monarchy. He flew back to Poland instructing my mother and I to go to Paris and to wait for him there. It would be almost two decades before I saw him again.

What happened when he returned to Poland?

Upon his return to Soviet-controlled Poland, he was appointed the CEO of the largest savings bank in the country—the PKO. He served in this post until 1956 when he tried to flee the country and was denounced by the same people that were supposedly helping him escape. He was accused of currency smuggling, but the real reason was because of his well-known sympathies with China. He was placed in solitary confinement. While he in prison he caught pneumonia and almost died.

Two years into his incarceration, freedom came from an unlikely source. The Polish government received a request from China asking for his release. My father later told me that Zhou Enlai, who was then China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, had a personal interest in his release.

My father was released from jail in 1958 and given a one-way ticket out of Poland. But no country would take him, including Mexico, where my mother had asked for and received political asylum. The effects of McCarthyism were still being felt at this time in Mexico. Having no other option, he returned to Poland, where he became a professor and wrote a dozen books, including a biography of Abraham Lincoln--the only US president he used to say was worth anything.

Did he ever return to China?

He never visited China again. For many years, the Polish government tried to send my father back to China, believing that if he was received again by Zhou Enlai that they could assert the role that Romania or Albania were then playing as a go-between China and the Soviet Union. My father, who after the Yalta Conference despised the presence of a Soviet sponsored government in Poland, refused.

When were you finally able to reunite with your father?

I saw my father for the first time since I was five years old when I flew to Poland in 1972. I was 25 years old. I then returned several times to visit him.

In 1978, I was leaving Japan, where I was in the diplomatic service working for the Mexican government, and decided to stopover in China. I wanted to update my father on how China had changed more than 30 years after he had been there.

Within a month of my last visit, my father passed away. Had the Chinese government not intervened all those years ago, I may never have seen my father again. I owe the Chinese government and Zhou Enlai my father’s life.

Did you ever find evidence of correspondence between your father and Zhou Enlai?

I have sadly never found the letters between Zhou Enlai and my father. When we looked through his apartment, after his death, we didn’t find anything and I imagine the Polish authorities might have taken everything.

While teaching at NYU Shanghai, I went to Beijing and tried to trace my father’s footsteps through the archives there, but much is locked away and it has been difficult to confirm whether everything I have in my memory about what my father told me is fact. But I am comforted by something a friend of mine once said: ‘The word is much more than the documents. This is your story as told to you by your father, and what you remember from him is more important than all the research you can find.’

Above Left to Right: Jan Drohojowski presenting his credentials in Egypt; Francisco Drohojowski, aged 3, pictured with his father in Mexico